Readers who don’t have a Science subscription can access a pre-formatted version of the manuscript here. In this post I wanted to give a brief overview of the study and then highlight what I see as some of the interesting messages that emerged from it.

First, some background

This is a project some three years in the making – the idea behind it was first conceived by my Sanger colleague Bryndis Yngvadottir and I back in 2009, and it subsequently expanded into a very productive collaboration with several groups, most notably Mark Gerstein’s group at Yale University, and the HAVANA gene annotation team at the Sanger Institute.

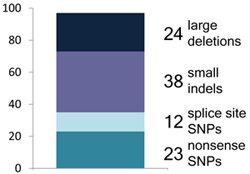

The idea is very simple. We’re interested in loss-of-function (LoF) variants – genetic changes that are predicted to be seriously disruptive to the function of protein-coding genes. These come in many forms, ranging from a single base change that creates a premature stop codon in the middle of a gene, all the way up to massive deletions that remove one or more genes completely. These types of DNA changes have long been of interest to geneticists, because they’re known to play a major role in really serious diseases like cystic fibrosis and muscular dystrophy.

But there’s also another reason that they’re interesting, which is more surprising: every complete human genome sequenced to date, including celebrities like James Watson and Craig Venter, has appeared to carry hundreds of these LoF variants. If those variants were all real, that would indicate a surprising degree of redundancy in the human genome. But the problem is we don’t actually know how many of these variants are real – no-one has ever taken a really careful look at them on a genome-wide scale.

Read the rest of this entry | Read comments